Service time refers to the number of days a professional athlete has spent on a team’s active roster or injured list, and it plays a critical role in contract eligibility, free agency, and arbitration rights, especially in MLB.

In most leagues, it’s a backend metric. In baseball, It’s the whole game. The manipulation of service time is one of the most controversial and financially impactful elements of modern sports contracts.

How Service Time Applies In Different Leagues

⚾MLB

MLB service time is tracked in days, and 172 days of service = 1 full year.

A player needs 6 years of service time to hit unrestricted free agency.

Use Cases

- Teams manipulate call-up dates to keep players under the 6-year mark for an extra season of control.

- Once a player hits 3 years of service (or qualifies as a Super Two), they become arbitration-eligible.

- Players accrue service time even while on the injured list.

Example

The Kris Bryant Case became a service time scandal. The Cubs kept him in the minors for just 12 days in 2015, saving a full year of control and delaying free agency until 2021.

Bryant filed a grievance, lost, and played 7 years before entering the market as a free agent.

🏈NFL / 🏀NBA / 🏒NHL

These leagues don’t have “service time,” but they do have structured “Years of Service” and “Team Control” periods.

How It Works

“Service time” here means how many years a player has on an active roster, impacting:

- Free agency eligibility

- Restricted vs Unrestricted rights

- Contract options

- Minimum salary tiers

- Pension and benefit qualification

Each league defines it differently, but the purpose is the same:

teams maintain control early, players gain leverage later.

Use Cases

NFL

- 3 years = RFA (Restricted Free Agent)

- 4 accrued seasons = UFA (Unrestricted Free Agent)

- Team control exists via rookie deals, 5th-year options, tags

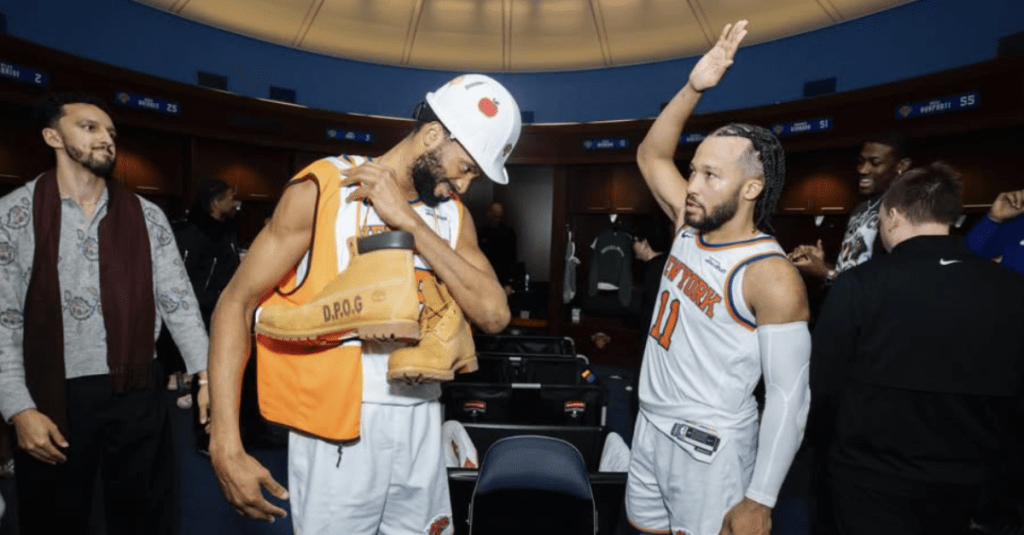

NBA

- 0–4 years = first contract scale (restricted rights)

- 4+ years = veteran contracts

- Bird Rights and Early Bird Rights build via years of service

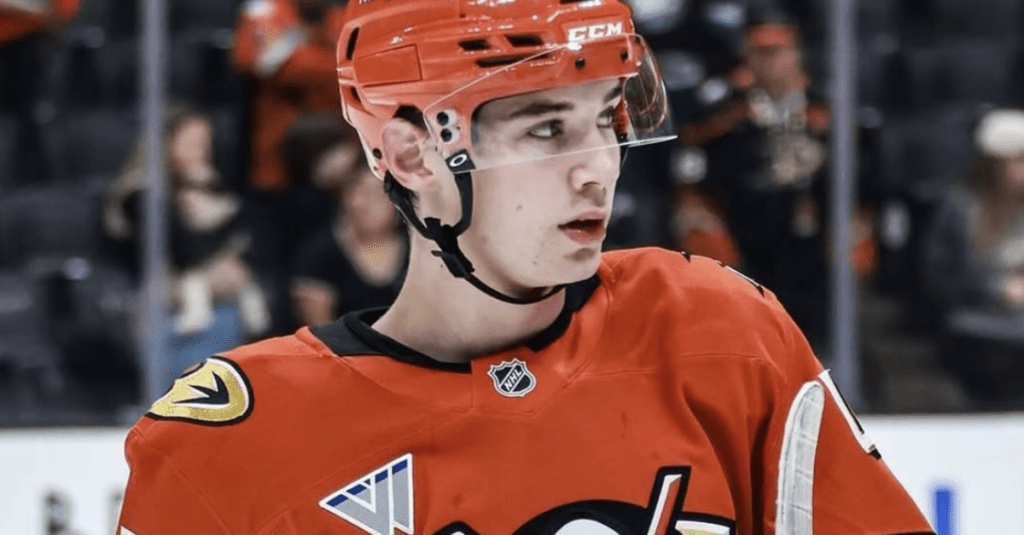

NHL

- “Entry-level slide” rules

- RFA status based on age + accrued seasons

- Arbitration rights triggered after set years

All are different ways of measuring player eligibility → player leverage → financial power.

Examples

- NFL: A 4th-round rookie gets 4 years of team control. Only after four accrued seasons can he negotiate freely.

- NBA: A player on a rookie-scale deal hits RFA after Year 4, giving the original team matching rights.

- NHL: A young star may play 2–3 years before gaining arbitration rights, but the team still owns RFA status and control.

It’s not “service time,” but it’s the same logic: Teams keep players cheap early → players get paid once they’ve “served” enough time.

⚽MLS & International Soccer

Soccer does not use “service time” the way MLB does, but they do have equivalent control mechanisms.

How It Works

Soccer doesn’t track service time for arbitration or free agency. Instead, player “control” is dictated by:

- Contract length: 2–5 years is standard

- Team-owned rights: MLS Homegrown, Discovery Rights, etc.

- Training compensation & solidarity payments: FIFA rules protect clubs that develop the player.

- Age-based restrictions: young players can’t freely transfer without fees unless out of contract.

Once a player signs a pro deal, the club controls his rights for the length of the contract, and contracts can be extended, sold, or loaned.

Use Cases

Soccer teams use contract control to:

- lock in young talent before their market blows up.

- sell players for profit instead of letting them leave for free.

- manage salary budgets in MLS.

- control loan agreements to build value.

- protect academy development pipelines.

- time transfers to maximize ROI.

It’s not “service time,” but the effect is identical: teams control players longer than the players control teams.

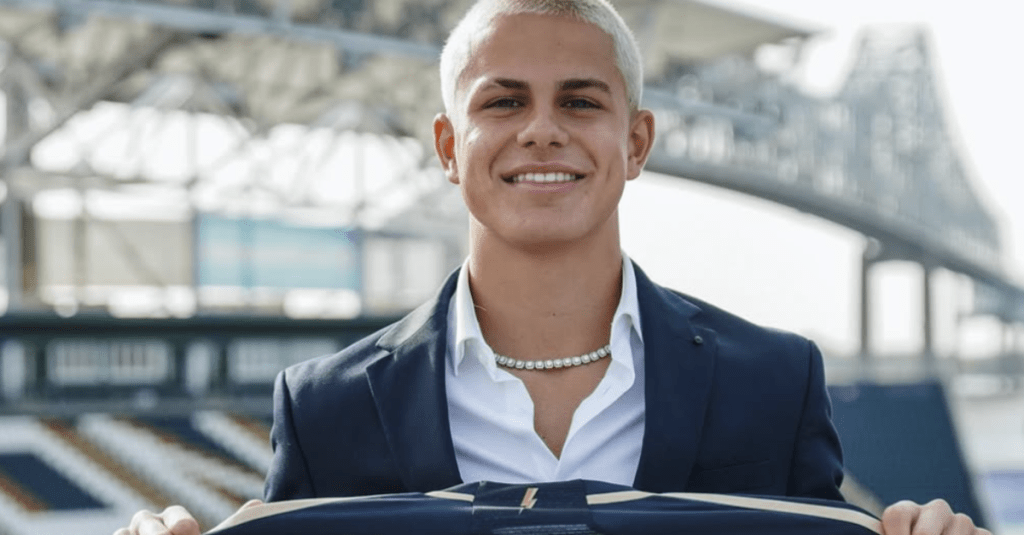

MLS Example

A Homegrown player signs at age 17 on a 3-year deal + 2-year club options.

The team effectively controls his rights for up to 5 years before needing to renegotiate with the , the MLS version of a long control window.

International Example

Erling Haaland joined RB Salzburg on a modest contract, but because they controlled his rights, they sold him for a massive profit to Borussia Dortmund rather than losing him for free. No “service time,” but identical competitive logic: team control → maximize ROI.

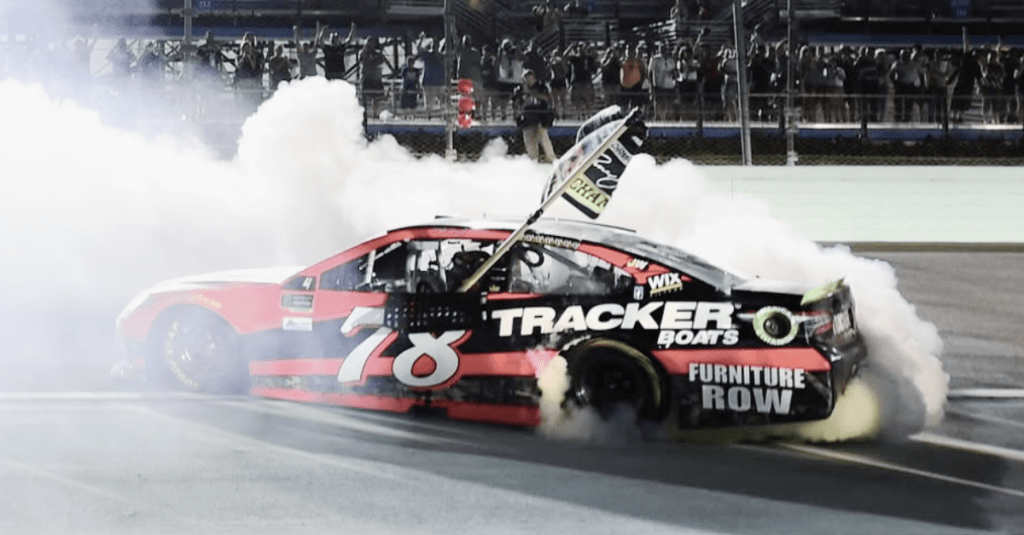

🥊Combat Sports / ⛳Golf / 🏎️Racing

Service time doesn’t apply to individual sports like UFC, golf, tennis, or racers in the same way.

These sports’ athletes are on event-based contracts, not seasonal employment/official contracts.

Use Cases

- UFC/Combat: Fighters gain leverage through activity and win streaks.

- Golf/Tennis: Rankings and earnings dictate access, not service length.

- Racing: Race starts and championship points matter more than service years/years on a team.

Example

In F1, Lewis Hamilton’s experience (aka “service time”) gives him leverage in contract talks, but it’s not formalized into CBA-like thresholds.

Why Service Time Matters

In leagues like MLB, it’s a power tool used by front offices to delay free agency and retain cheap labor.

For players, it’s a career clock and a source of frustration when its manipulated.

Service Time Affects

- When a player gets paid market value.

- When they become eligible for arbitration or free agency.

- How long a team can control a player’s rights.

Fans often don’t realize the financial impact of holding a player in the minors for 2 extra weeks.

But, that move can mean tens of millions of dollars lost for the athlete over their career.

With the average pro sports career being under 7 years and over 70% of athletes going broke within 5 years of retirement, players want to maximize their earnings as much as possible. Service time is the invisible hand that controls the timeline of a sports career.

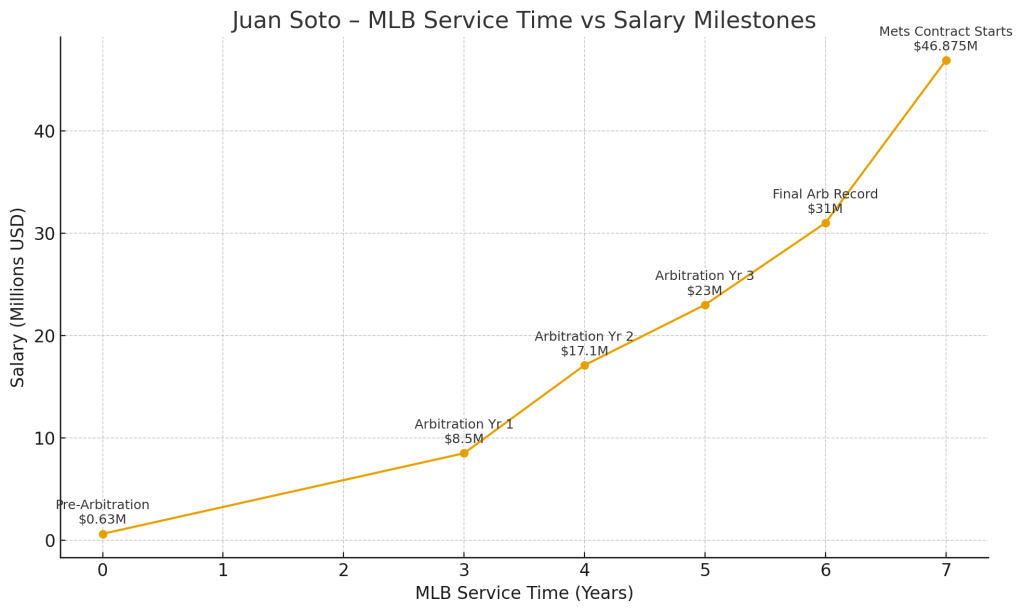

📊Graphic

🔗Related Terms

🔗Next Reads

- Juan Soto Signs the Biggest Contract in MLB History

- Highest-Paid MLB Players of 2025

- How the NFL Franchise Tag Works Financially

- NBA Salary Cap Explained

- Top 5 Longest NHL Contracts In History

“Do not grow weary in doing good,

for at the proper time we will reap a harvest if we do not give up.”

— Galatians 6:9