In athlete economics, the private jet has quietly become one of the most misunderstood luxury assets.

It shows up on Instagram as a symbol of arrival, but in the balance sheets, residency decisions, and endorsement negotiations of modern athletes, the jet can function more like infrastructure than vanity.

The catch is that infrastructure only makes sense when the athlete actually has a business to support it.

The last five years in sports culture have collapsed the gap between “actually making it” and “looking like you’ve made it.”

NBA rookies are now chartering jets before their second contract.

UFC fighters with fewer than five pay-per-view appearances are for some reason renting jets for media week and promotional events.

MLS and International soccer players with modest base salaries and lifestyle sponsorships are using fractional programs for offseason travel and content production.

The jet isn’t about convenience; it’s about time, brand, and perception, three things athletes monetize aggressively and for the short window that pro careers average.

Early-Career Strategy

For veteran and star athletes, private travel was historically defensive, used to protect the body, protect recovery and thus, protect the season.

For rising athletes, it has shifted into offensive strategy.

Private jets save time in the literal sense (layovers, security, fan exposure, unaligned routes) but also in the business sense, compressing schedules between brand shoots, training blocks, offseason residencies, and corporate activations or league meetings.

Time is a scarce currency in pro sports. A 21-year-old with an eight-year prime doesn’t think like a 55-year-old CEO with three decades to compound returns.

Athletes monetize windows.

Rappers, fighters, basketball players, most pros now understand this intuitively, that their max-earnings window closes fast, and a jet can make or break said window.

Jets Are Capital-Hungry and Depreciating

None of the branding halo changes aviation economics.

Jets are expensive to buy, expensive to maintain, and expensive to operate and unlike homes or commercial real estate, they do not appreciate.

Most private jets depreciate between 5–10% per year (worse than cars), with sharper curves in the first 3–6 years of ownership.

A $10 million midsize jet losing 7% annually burns ~$700,000/year in value before fuel, hangar, pilots, or maintenance enter the equation.

Add in fixed costs: hangar rent, crew salaries, insurance, training and regulatory compliance.

Those can land between ~$400,000–$1,000,000+ per year, depending on aircraft class and region, even if the aircraft never leaves the hangar.

Then add fuel and maintenance, which for midsize or heavy jets land in the $3,000–$7,000/hour range when factoring in overhauls, landing fees, and engine reserves.

Usage determines sanity.

Brokers quietly admit the threshold:

- <75 flight hours/year → ownership is irrational and a wealth killer

- 75–250 hours → fractional or jet cards make sense

- 250+ hours → ownership begins to make financial sense

Most rising athletes sit somewhere between 20–80 hours needed and don’t have the ability to afford their own jet, hence why teams take on that cost for the season and mandatory meetings or events.

Many Athletes Don’t Own the Jet They Flex

It’s not a secret in aviation: the majority of younger athletes don’t own jets, they rent them.

The content looks identical, the economics do not. Chartering converts the jet from a balance sheet asset into a variable expense.

It removes depreciation, fixed burn, maintenance, and crew liability.

A fighter can charter for media week, a basketball rookie can charter for offseason training in Las Vegas, a soccer player can charter for a brand shoot in Europe. They get 90% of the perception with 10% of the commitment. In most cases, jets aren’t even paid for by athletes.

Brands, sponsors, or promoters may cover aviation as part of an activation budget. Combat sports use this constantly, the fighter arrives in a private jet for weigh-in and embedded content, but the promoter swallowed the aviation line as marketing spend.

Influencers figured this out earlier than athletes, rent the symbol, keep the capital liquid, monetize the content, avoid the depreciation.

Case Studies

This dynamic isn’t theoretical, it has already reshaped multiple sports.

Combat Sports

Fight weeks in boxing and MMA are built around media, press conferences, and sponsored appearances.

Chartering reduces fatigue and increases availability for activations.

This adds direct revenue. The window is tiny, a fighter might only have 3–6 lucrative pay-per-view opportunities in a career.

A jet that protects those is not luxury; it’s career and wealth insurance.

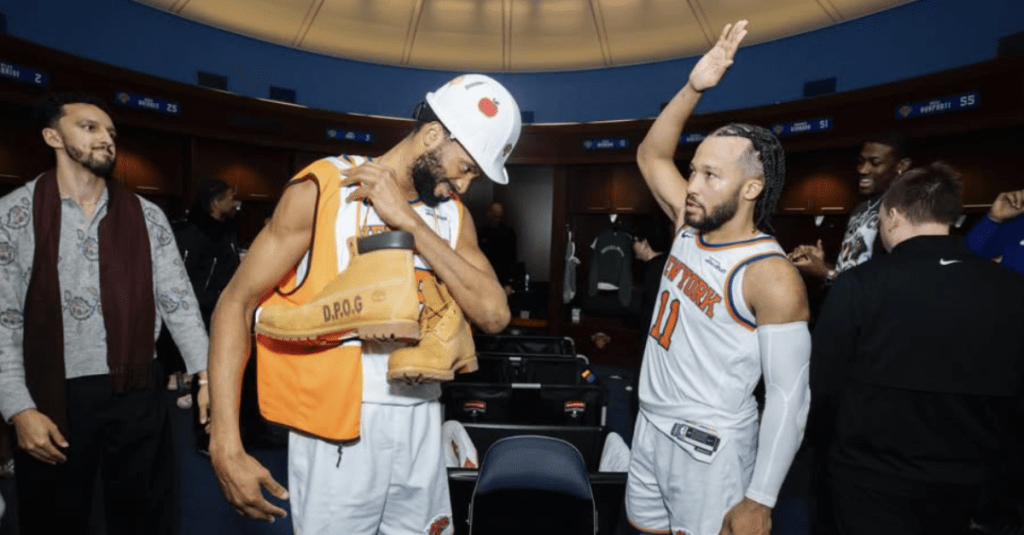

Basketball (NBA)

NBA players have extreme offseason volatility. Training in Los Angeles, charity events in hometowns, fashion week in Paris, brand shoots in New York.

Jet access allows players to stack activations instead of choosing between them.

That’s time arbitrage, not flexing.

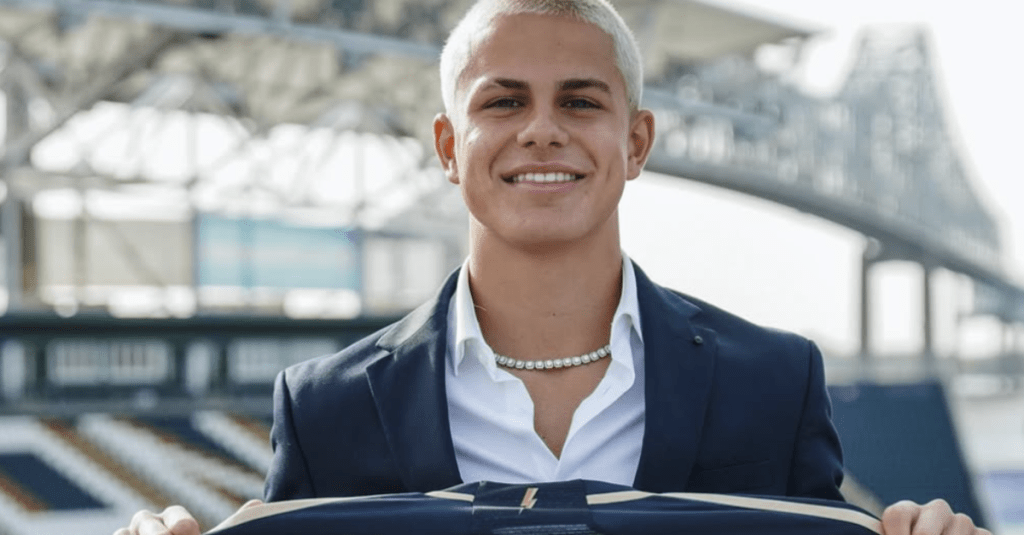

Soccer (MLS/International)

European-based players with U.S. endorsement portfolios use private travel to compress transatlantic brand work.

For certain forwards and wingers, lifestyle earnings rival or exceed salary. The jet protects the lifestyle portfolio, not the matchday.

Baseball (MLB)

Longer seasons, unpredictable travel, and sponsorship obligations make private access a fatigue hedge.

MLB players have enough runway (162 games + travel + All-Star + postseason + offseason) to justify ~100+ hours of annual usage in niche cases. Nearly all of these scenarios support access, not ownership.

The Tax & Residency Layer

Very few people talk about the tax side of jets but it matters.

Private aviation supports residency optimization, athletes live in tax-friendly states and commute to their markets. A Florida or Texas residency with heavy endorsement income can materially outperform living in California or New York once you factor in federal + state + FICA + agent fees + jock taxes.

The jet becomes a tool to maintain residency while fulfilling contracts, and that’s worth real net dollars.

A basketball player on a $12 million salary with $5 million in endorsements might save seven figures annually by maintaining Florida residency and commuting to Los Angeles or Brooklyn when necessary.

Again: that isn’t luxury.

That’s asset protection.

Financial Risk: When Flexing Outpaces Earnings Potential

The danger appears when status overtakes strategy.

Without brand premiums, sponsorship leverage, or scheduling demand, the jet becomes a liability.

Fans sees glamour; athlete accountants see deteriorating capital, lumpy cash flow, underutilization, and opportunity cost.

The worst-case scenario is a young athlete who buys a depreciating asset during early-career cash spikes, then watches their income flatten or collapse due to performance, injury, role change, or market saturation.

Luxury assets do not adjust downward, they expect fuel, pilots, hangars, and maintenance whether the checks clear or not.

That is how jets go from status symbol to cautionary tale.

Is the Jet an Asset or a Liability?

For most rising athletes, the smartest answer is neither, the jet is access, not ownership.

Access maximizes perception, brand, and efficiency without forcing aviation economics onto a short earnings window.

Ownership only makes sense when:

- schedule justifies 200+ hours

- brands subsidize the halo effect

- the residency and tax strategy demands mobility

- capital base is durable

- endorsements are premium

- earnings are predictable + decades-long compounding potential

Without those, the jet is an expensive costume in someone else’s movie.

Jets Outlook

The private jet is the cleanest test of athlete financial intelligence.

It separates the player who understands they are running a business from the player who thinks they are living a lifestyle.

The irony is that the jet becomes most rational only when the athlete stops treating it like a flex.

Status without structure is liability.

Status with structure is leverage.

For the rising athlete, the winning play isn’t to buy the jet, it’s to use the jet as a prop, a tool, and a bridge to bigger deals while keeping the core capital compounding somewhere that doesn’t lose 7% a year in depreciation.

Why a $100M Pro Contract Only Nets $35–$55M

Enjoy Reading How Money Works In Sports?

The APSM $100M Pro Contract Report Includes:

- contract structure analysis

- Taxes, agent fees, and escrow

- Endorsement and bonus scenarios

- Investment retention & wealth building strategies

- Real-world case studies of player earnings vs take-home

Everything you need to understand how multi-million dollar contracts translate into actual wealth and how to avoid common financial pitfalls.

Next Reads

- Why U.S. Investors are Buying European Soccer Clubs

- Dick’s Sporting Goods Acquires Foot Locker

- Nike’s Tariff Problem: How U.S. Trade Policy Reshaped the Swoosh’s Margins, Endorsements, and Global Strategy

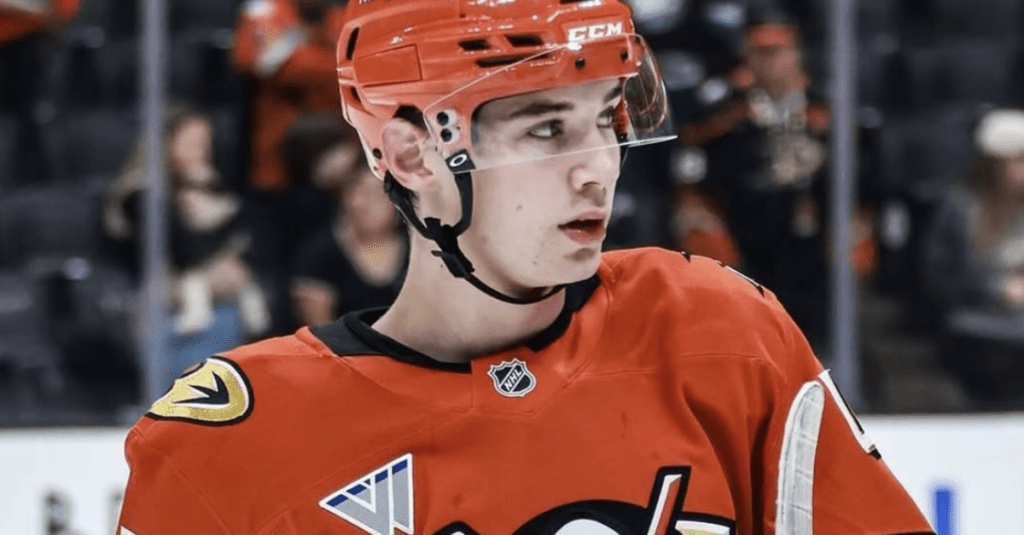

- How NHL Players Get Paid Compared to Other Leagues

- Inside Juan Soto’s $25 Million Beverly Hills Mansion

Credits

Written By: Aidan Anderson

Research & Analysis: Apostle Sports Media LLC

Sources: Aviation Week, NetJets Public Materials, FAA Filings, Orizair Brokerage Data, SOLJETS Listings, Forbes Council, Business Insider, APSM Proprietary Analysis.

Featured Image: Public Domain / Wiki Commons

Disclaimer: This article contains general financial information for educational purposes and does not constitute professional advice.

I will not leave you as orphans;

I will come to you.

John 14:18